A Technical Analysis of the Claims in Johnny Patience’s The Zone System is Dead

“Reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.” - Mark Twain

1.0 - Introduction

Whether I shoot film or record a digital file for projection, I use the Zone System. In Death of the Zone System II, I explained how I learned ZS and the benefits it conferred on my photographic process. In pre-production on Deadwax, a ShudderTV original, I used Zone System to create a set of in-camera Look-Up-Tables for the digital camera in order to confidently set lights with a light meter. Speaking in photometric values with my gaffer, Katie Walker, allowed us to work quickly on set without being tied to the monitor, and easily manifest our aesthetic in the post-production pipeline. Stumbling upon Johnny Patience’s The Zone System is Dead I was surprised to learn the very methods I use for controlling exposure and tonal representation are fatally flawed, irrelevant in the 21st century, and thereby dead. Should I throw away my notebooks, calibration tablets, charts, densitometer, and light meter? The flattering and enthusiastic comments section following the Zone System is Dead would lead one to believe Patience’s discovery is a resounding success. I e-mailed a list of technical questions, terminology clarifications, and a request for his photographic tests and never received a response. I submitted the same list of questions in the comments section of the blog which, unsurprisingly, were never posted. As of this date I still have not received any answer.

I am genuinely interested in the sequence of steps and tests that support his conclusion because subjecting my own research to counterarguments or conflicting experiments is the forge from which to shape new ideas. However, a lack of response implies that his article exists in an echo chamber. I decided to move forward with posting this piece since the ideas in The Zone System are Dead are common misconceptions I find on the internet. Patience’s ideas are persuasive to those who have never or only briefly researched Zone System. To address this imbalance I have written two pieces sketching the basic process of how ZS works on a theoretical and technical level. On a practical level I’ve also written a section explaining how to calibrate photographic materials using ZS.

By presenting the technical principles and working practices of ZS along with the science of sensitometry I hope other photographers can reach their own conclusion about whether this is a tool worth their time and energy to learn. I gave up controlling the length of this piece because it contains a number of elementary sensitometry concepts that would benefit both beginners and experts. Towards the end of this piece I will explain how I can use ZS and sensitometry to interpret what exactly Patience’s photo process and metering method accomplishes (and what it does not) to provide a fair sense of perspective.

2.0 – Finding the Logical Argument

Overall, the majority of Zone System is Dead is filled with far more anecdotes, opinions, and emotionally stirring rhetoric than clearly explained concepts and scientifically backed claims. While my argument is with the latter it is imperative to identify these rhetorical techniques in order to preclude them from future discussions.

Patience relies on emotionally charged language to make two arguments. First, he paints those who use and understand Zone System as “traditionalists” and worshippers of a “Holy Grail of B&W” that “repeat golden rules without questioning.” This is a biased characterization of ZS users as blindly chasing an unattainable end. There is no “tradition” in using what is simply a tool for tone control in a photographic system. Also, there is no ultimate summit of perfection, but rather a process of refinement that allows for more creative control. I imagine that the enthusiasm by some photographers for ZS has led the author to take an emotional stance.

Secondly, he dismisses ZS as too complex to understand with a cursory “you can forget about it now (in case you didn’t ever completely understand or like it anyway).” I agree that the methods and practices have a steep learning curve (all puns intended). However, the principles are easily learned by anyone who applies their mind and energy to the task. Often the most valuable lessons in any field are not the easiest. I can hear echoes of Euclid’s “there is no royal road to geometry.” Similarly, there is no royal road through Zone System.

There is also a great deal of anecdotal evidence offered up in this article that lacks substance. There is an appeal to authority in commenting that Paul Caponigro and Gary Briechle agree with his conclusion. This is poor evidence without direct quotes or the context of the conversation. I have to admit that if someone ran up to me on the street and asked “is it okay to overexpose my negative film by a stop or two?” I would respond in the affirmative. If they asked “is overexposing my negative film a stop or two the best method to control tonality in my photographic system” I would respond in the negative. We just don’t know enough about these conversations to warrant it as proof. Also, ZS is not used by all photographers. So identifying two photographers who don’t use ZS just means you found two photographers who don’t use ZS.

Anecdotal evidence extends to the author’s claims he “…researched the topic in depth, shot hundreds of rolls of B&W film, experimented with all kinds of exposure settings, chemicals and development formulas.” However, the article curiously lacks any specific evidence from all this research and testing. This is important because Patience’s criticism of ZS and the technical claims about his metering method are ultimately researchable and scientific.

With emotion and anecdotes aside does this article warrant conceptual and technical merit? I contend Patience’s explanations of Adams and Archer’s concepts and method are flawed. The author mischaracterizes the concepts and practices of ZS to buttress his argument, fails to provide sufficient evidence to back up his claims, makes erroneous technical claims about film technology and sensitometry, displays a lack of knowledge of the history of photographic materials, and over-exaggerates the importance of his metering method. No laws of physics are being broken here contrary to his humble claim in the opening paragraph. Unfortunately, for the reader, his technical obfuscation provides little educational content to help others improve their photography.

2.1 The Argument

I find it useful to represent any argument in logical form in order to more clearly understand the claims and their connections. I understand his argument as follows:

Premise 1 – A photographer can achieve excellent results with negative film by overexposing it many stops above the manufacturer’s ISO.

Premise 2 – The results of Premise 1 are in direct contradiction to the concept and methods of using Zone System.

Conclusion – Therefore, Zone System is fundamentally flawed, i.e. dead.

I will begin by looking at Premise 2 because we need to carefully define Zone System versus how Mr. Patience explains it in his article. Once we clarify the concepts and methodology of ZS we can return to the first premise in order to understand his exposure method.

3.0 Zone System versus Patience’s Portrayal of Zone System

The claims about Zone System and how it works are scattershot throughout the article and require consolidation. For clarity I have isolated Patience’s claims in italics within indented paragraphs. His ZS claims fall into four essential categories:

Claims about Zone System’s relevancy to modern photographic materials. I will call this the “out-of-date” argument.

Claims about the methodology of ZS in relation to metering.

Skepticism that tonality is controllable from scene to print.

The claim that ZS does not allow for subjectivity.

3.1 Zone System is “Out-of-Date”

“[Zone System] … is based on late 19th century sensitometry studies and it provides photographers with a systematic method of precisely defining the relationship between the way you visualize a photographic subject and the final results.”

The definition the author provides is fairly accurate and a nearly verbatim copy from this wikipedia entry. What exactly is the problem, then? There is a sense that Patience is leaning into the idea that Zone System is “based” in an archaic 19th century science. I think the author of the Wikipedia entry is partially to blame because the choice of wording seems to directly correlate the beginning of sensitometry and zone system. There is a distance of decades between the pioneering work of Hurter and Driffield and the sensitometry techniques and tools when Adams and Archer created the Zone System. Zone System came into existence in the late 1930s and was refined throughout the 1940s and 50s. By then there were great improvements in standards of measurement, definitions, and the accuracy of the tools. Adams writes in his autobiography “For technical confirmation, I asked Dr. E.C. Kenneth Mees, director of the Kodak laboratories, and Dr. Walter “Nobby” Clark, his associate, to check the accuracy of the Zone System and its codification of the principles of applied sensitometry. Their favorable comments supported and encouraged me.” (Adams, 1976 pg. 275) Work on sensitometry and ZS did not end there and were researched and updated throughout the 20th century.

Here are two better definitions of the science of sensitometry that frame its methods and aims more clearly. The science of sensitometry is “the scientific method of evaluating the technical performance of photographic materials and processes in the recording of images.” (Eggleston, 1984 pg. 1) Studying sensitometry “…provides the necessary understanding of the technical characteristics of photographic films and papers. It deals with all aspects of the original subject to the finished image.” (Stroebel, et al., 1990 pg. 86) Notice that these two definitions establish an important hierarchy - that photographic materials and processes are studied through the science of sensitometry.

“Everything evolved since 1930, and that includes photographic film, chemical emulsions and photographic paper.”

“…new film emulsions and papers [sic] stocks changed the technical base the Zone System was once founded on.”

These statements identify two issues that should be examined more closely; one involving the nature of science, and the other involving Zone System’s relationship to sensitometry.

The sciences are founded on establishing general principles from research on particular instances. As a science, sensitometry studies the wide range of possible photographic materials from the past to the present. Patience is making a bold claim that a change in emulsion formulas changed the technical base (aka - sensitometry) that ZS was founded upon. In order for this statement to be true Patience needs to furnish proof of an exact change in a photographic material resulting in a fundamental change to the science. If a film manufacturer changing materials and chemicals undermines Zone System then the whole method would have fallen apart immediately.

Improvements to emulsions, chemistry, and materials (whether in dynamic range, grain, and sensitivity) are all analyzed and understood through the science of sensitometry. Patience’s statements are reversing this relationship. This is similar to claiming that ‘the fact car engines are now cast from aluminum alloy and no longer iron alloy disproves the principles of the combustion engine.’ The author is inverting the relationship between general principles and specific instances in an effort to sow doubt in the reader’s mind.

The second issue concerns the relationship between sensitometry, Zone System, and photographic materials. When an artist makes a photographic image they are engaging with the fundamental science of sensitometry. This science encompasses general principles of tone reproduction and is modified slowly over time through research and engineering. Zone System is a practical method for photographers to apply sensitometric concepts to their specific materials. Simply, Zone System is an interface between the general and the particular.

Diagram 3.1 - Sensitometry is the foundation for understanding the behavior of photographic materials - especially in regards to tone reproduction. This science is largely stable and changes little over time. Zone System operates as an intermediary, allowing us to apply sensitometric principles to the photographic medium using our visual system as the conduit. Finally, above these are the ever changing photographic materials and tools of the art and craft.

Patience is obscuring this hierarchy by confusing methods and materials. As a method Zone System is the application of general sensitometry concepts to the particular case of each photographic process. As a method Zone System gives a photographer the ability to take into account the immense number of variables unique to each photographer’s process to facilitate their vision. The photographic materials themselves are the subject of study. Changing photographic technology is a foregone conclusion and all it takes (whether one uses ZS or not) are a few tests to learn how new materials perform in order to adjust one’s process. What is lost in the obsession over materials is that ZS helps photographers apply sensitometry without the need for expensive (and now hard to obtain) step wedges and densitometers. The revolutionary feature of ZS is that it works on a visual level using the acute perception of the photographer.

“…Adams’ findings seem to make sense if you only consider the traditional darkroom process and have never worked with a scanner or multigrade paper.”

Instead of providing evidence how changes to materials impact the fundamental methods of ZS, Patience instead offers up this opinion. He fails to explain how multigrade paper is not a “traditional darkroom process” or how its existence disproves Adams and Archer’s methods. Graded photographic papers existed at the time of Zone System’s creation. Adams discusses graded papers in The Negative (1981, pg. 47) and The Print (1983, pgs. 47-48). The New Zone System Manual covers paper grades as a part of the system. (1976, pg. 71) The methods of testing graded papers for ZS are covered extensively in Davis’ seminal Beyond the Zone System. (1988, pgs. 115-118)

Explanations of how multigrade papers are integrated within ZS is easily located by consulting the index of any of the books cited in this article. ZS practitioners calibrate for multigrade paper using a middle grade in the ranges possible (typically Grade 2, but I know others who use Grade 3). Starting in the middle means the photographer has options for changing the contrast of their image. Most importantly, there is a technical advantage to calibrating to the middle contrast grades because dodging and burning adjustments on higher grades produce rapid changes in tonality, making it difficult to manually execute tonal changes. On the other side calibrating to a low contrast grade simply does not provide any practical benefit to the photograph (1981, pg. 47). The weight of textual and practical evidence multigrade paper is integrated into ZS and there is a logic to its use. The author’s claim that this doesn’t ‘make sense’ is an empty declaration.

The flexibility of ZS methods extends to digital and even hybrid digital/film systems. Users can calibrate digital systems by performing under/over exposure tests and establishing a basic workflow changing only one variable at a time. This is tricky with digital because of the sheer number of options and settings made available in scanning and image processing software. Nonetheless, there are books currently in print detailing how to calibrate ZS for digital that contain information on scanning. While I personally don’t use a scanner I have a theoretical understanding of how I could incorporate the scanner into my system. This would involve scanning a calibrated step wedge (or even an over and underexposed graycard) in order to find the minimum level of density that the scanner is able to detect above the base+fog level. This would determine the exposure index of my film and from there I could experiment with optimal developing times. I don’t have the space to go into specifics but perhaps a clear article could be written about this in the future. (Note to self.)

The fact that Hurter and Driffield developed sensitometry and Adams’ and Archer created Zone System with analog materials is mere historical fact. Sensitometry and ZS would have lived a short life if they were rigidly tied to a specific set of photographic materials. Instead, the concepts developed by these pioneers are more general and encompass the photographic process in its many material expressions. The flexibility of Zone System as a method to understand and control a wide range of materials is pointed out by Minor White, Richard Zakia, and Peter Lorenz in the Author’s Preface to the The New Zone System Manual:

“Photographic chemistry is changing. Equipment is in the throes of automation. Weston exposure meters are phasing out. As foolproofing advances, Contrast-Control diminishes. But the principles of sensitometry upon which the Zone System stands, remain firm. And visualization always has the creative power to accommodate whatever changes are ahead.” (1976, pg. 2)

The “out-of-date” argument is mere handwaving to distract from clearly explaining the relationship between the materials and the science.

3.2 Metering

“The most common problem in film photography is underexposure. Not because metering is more difficult than with a digital camera, but because all light meters are using medium gray as their point of reference.”

“Metering for neutral gray often makes shadow areas fall into the wrong range, or if you like, zone.”

These statements cast a lot of suspicion on light meters. My best guess is that he is speaking specifically about the reflective meters internal to cameras. Cameras with internal meters typically average the light across the frame (this averaging can take many different forms) which can produce undesirable results. For example, if your frame is mostly a bright sky then the meter will underexpose. This can be seen with cellphone cameras in auto-exposure mode. However, an averaging meter failing to produce the exposure the photographer desires is neither a ZS problem nor the meter’s fault.

First, to describe all light meters as using “medium gray as their point of reference” is inaccurate. Light meters, whether incident or reflective, quantify the amount of light collected by the photocell as a photometric quantity. Incident meters quantify the illuminance falling on the dome of the meter, whereas reflective meters quantify the luminance averaged across an angle of view. Light meters use a photometric quantity as their point of reference, not middle gray.

The photometric quantities are then calculated into an exposure time and f/stop based on the ISO. At this moment we do need to draw an important distinction between incident and reflective meters. Incident meters produce exposure information so that objects under the same incident light will maintain their tone. An incident reading in front of a white, black, or middle gray object all produce the same f/stop and exposure time provided all the objects are under the same intensity of light. Obviously, these meters are not taking middle gray as their reference. However, reflective meters do require exposure calculations to turn luminance into exposure values of a particular tone. The decision by the ISO committee was to make incident and reflective meters agree. This decision is of immense practical value because it equates an incident reading in front of a graycard to the reflective meter reading from the same graycard.

Diagram 3.2 - A visual explanation of how illuminance (in footcandles) and luminance (in candelas per feet squared) are transformed into camera settings. The ISO made the thoughtful recommendation to equate incident readings to reflective readings from a graycard. I chose these numbers from the 100:100:2.8 rule in cinematography - that 100 footcandles, at 100 ISO is correctly exposed at f/2.8. (Assuming 24fps and a 180 degree shutter!)

The author’s complaint is that underexposure is a problem tied to the fact that reflective meters are calibrated to make the tone of an object middle gray. This begs the question - what tone would he prefer reflective meters to render objects? White? Black? A particular dark or light shade of gray? If this was the case we would need to remember that the incident meter is accomplishing one exposure goal, while the reflective meter is accomplishing quite another. This “controversy” is addressed very adeptly in Basic Photographic Materials and Processes.

“It may strike the readers as strange that, whereas film speeds for conventional black-and-white films are based on a point on the toe of the characteristic curve where the density is 0.1 above base plus fog density, which corresponds to the darkest area in a scene where detail is desired, exposure-meter manufacturers calibrate the meters to produce the best results when reflected-light readings are taken from midtone areas. Meter uses who are not happy with this arrangement can make an exposure adjustment (or, in effect, recalibrate the meter) so that the correct exposure is obtained when the reflected-light reading is taken from the darkest area of the scene, the lightest area, or any area between these two extremes. This type of control is part of the keytone method and the Zone System. (1990, pg. 56).

What the authors of this text are proposing is not radical - that a human with a brain should interpret the data of the meter to their photographic needs. Moreover, they observe that there are systems in place to assist the photographer in this task, namely keytone and Zone System. Patience’s criticism of ZS is a tacit admission that he is ignoring the very tool that would help solve his reputed “meter problems.”

3.3 – No Correlation Between Zones in Subject and Zones in Print

“The biggest misconception resulting from the zone system is the suggested correlation between tonal values in a scene and tonal values in your print or scan. There simply is no such correlation.”

The gravest claim that strikes at the heart of Zone System is that there is no “correlation between tonal values in a scene and tonal values in your print or scan.” This is supported by an anecdote about how exposure to a dark and moody scene produces too thin a negative for a proper scan or print. The paucity of technical details in this example provides no evidence to support his criticism. When confronted with exposure issues in classroom settings we go over the students metering technique, camera settings, meter readings, and darkroom technique to assess what resulted in a thin negative. A vague story about underexposure does not present a case against ZS. In fact, to seasoned photographers this example suggests that the author made a mistake in metering and/or exposure - which is an easy suspicion considering his claims about metering.

There is another possibility for underexposure problems - the strong possibility that Patience never tested his film/developer combination to find its proper Exposure Index. One of the earliest steps required in learning ZS is to experimentally verify the exposure index (or effective film speed) of your film/developer combination. This guarantees that the lowest shadow detail in a scene meets a specific threshold of density on the negative. (Notice that this fact is mentioned in the previous citation from Basic Photographic Materials and Processes.) If you are interested in the process you can find a description of the process in Appendix of Adams’ The Negative, and in the Calibration chapter in the New Zone System Manual. I also wrote a sketch of Zone System Calibration here.

Calibration brings the Zones in the subject and print into alignment. The New Zone System Manual explains the virtues of rigorous calibrating and testing. “Consequently calibration and material testing is an on-going part of a systematized photographer’s career; because it keeps all variables under control, connects photographer to medium, makes visualizing possible and effective.” (1976, pg. 3) I can point to the materials in my ZS Calibration article in order to demonstrate that the Zones do in fact correlate. Look at how closely the graycard in my scanned print matches a graycard I placed on the scanner as reference. (Section 5.4) Patience never once mentions in his article attempting ZS calibration nor produces examples of how calibration failed to correlate zones. This lack of information is reminiscent of the Sherlock Holmes story Silver Blaze where the critical clue is that the dog didn’t bark. Patience’s statement that he has “shot hundreds of rolls of B&W film” while never producing a single technical counterexample should give the reader pause in believing the author’s claims.

3.4 Expose for Shadows and Develop for Highlights

“The mantra “expose for the shadows, develop for the highlights” reflects exactly that, and suggests to overexpose and underdevelop.”

The author’s claim that the ZS “mantra” suggests you overexpose and underdevelop is incomplete and incorrect. Compare this to the explanation in Basic Photographic Materials which points out that “…it can be seen in practice that the darker tones (shadows) should govern the camera exposure determination, while the lighter tones (highlights) should govern the idea of development. This idea is consistent with a common saying among photographers: “Expose for shadows and develop for highlights.” (1990, pg. 103)

Saying that this phrase only suggests overexposure is in line with his argument that underexposure is the greatest problem a photographer faces. However, this is a one-sided portrait because ZS practitioners choose between overexpose/underdevelopment, and underexposure/overdevelopment. Both techniques change how the film records the subject luminance range to match the limits of a print paper. Expose for shadows and develop for highlights cleanly encapsulates how the photographer uses exposure to set the minimum shadow detail point and uses development as a way to set contrast in a way that suits the intended aesthetic. In a technical sense, ZS users are determining exposure indices and development times for different contrasts in scenes so that their own ideas are realized appropriately and efficiently. Explaining only one half of Adams’ famous adage does a grave disservice to how cleverly this phrase encapsulates sensitometric principles.

“That in itself [the phrase “expose for shadows and develop for highlights”] doesn’t really make sense according to the Zone System, because it artificially changes the density and the tone curve of the negative.”

Patience is actually stating an opinion by claiming that exposing for shadows “doesn’t make sense” and is “artificial.” Changing the density and curve of the negative is precisely what the photographer must do in order to achieve an intended result. There is nothing “artificial” about it because the altered development time is the film photographer’s equivalent of using the ‘curve’ tool in Photoshop. For example, if the scene is too high in contrast for our given paper/film combination we pull the film (overexpose and underdevelop) to extend the exposure range of the film to match the paper and if the scene is too low contrast we push the film (underexpose and overdevelop) to compress the exposure range of the film to match the paper. The changing of our film rating/development time is just a tool available to us to achieve a desired tone rendering. If Patience is using the ‘curve’ tool in Photoshop he is a hypocrite since this too is “artificially” manipulating the tonality of his image by his own logic.

Patience’s claims that overexposing and underdeveloping does not work well with a scanner may well be accurate. However, he is not following the advice of Adams’ adage by calibrating his photochemical materials to the scanner. A ZS user would perform a calibration to the scanner in order to establish a proper exposure index and development time that suits the sensitometry of that specific device in particular settings. The author’s accusation that ZS users “repeat golden rules without questioning” is ironic in light of his poor explanation and misapplication of this famous adage.

3.5 Ultra-Deterministic Zone System

“It’s also not correct that darkroom prints are straight, unmanipulated results where the metered tonal value of the scene translates from the negative directly onto the paper. The photographer decides with each print how he would like to final result to look like and can adjust the brightness and the contrast of a print frame by frame…”

The use of an ultra-deterministic language is best exemplified by Patience’s claim that Zone System aims for an “unmanipulated” print where “tonal value translates from the negative directly onto the paper.” I am under the impression he is arguing that Zone System aims for a perfect print - one that does not require dodging, burning nor a change in contrast. This is Patience’s own dogmatic interpretation and is not a part of Zone System as explained in Adams’ books nor by subsequent experts. I challenge him to produce citations that support his claim.

I don’t think he’ll find his evidence because Zone System by definition and practice gets you to an “optimum” negative - a negative that is close to one’s previsualization and requires some, but not drastic tonal adjustments. (1981, pg. 47) Optimizing your process makes printing easier just as a properly exposed digital file is easier to correct in a computer. As I pointed out in my own experience, a print that is closer to my own previsualization wasted less time, less materials, and afforded me the time to focus on details. Adams’ himself produced the wonderful analogy that the negative is the composition and the print is the performance. A negative exposed and developed to ZS methods is like showing up to conduct an orchestra knowing the score and having an idea of how the piece should be realized.

3.6 It’s All Subjective!

One last criticism that should be dealt with is the notion that “it’s all subjective anyway” expressed in the “Darkroom prints are subjective” section. Invoking subjectivity is a lazy argument to let everything descend into a stew of relativity. What he fails to mention is that subjectivity is given a clear role integrated with the objective truths of sensitometry. This is addressed on page 1, Chapter 1 of The Negative.

“The concept of visualization set forth in this series represents a creative and subjective approach to photography. Visualization is a conscious process of projecting the final photographic image in the mind before taking the first steps in actually photographing the subject. Not only do we relate to the subject itself, but we become aware of its potential as an expressive image. I am convinced that the best photographers of all aesthetic persuasions "see" their final photograph in some way before it is completed, whether by conscious visualization or through some comparable intuitive experience.” (1981, pg. 1)

It is perfectly acceptable that Adams changed his printing of Moonrise Over Hernandez over time because his visualization also changed. The tools of the photographic medium are merely the vehicle for artistic expression. Similar to the author’s mistaken inversion that places sensitometry at the mercy of photochemical tools, he is placing the artistic vision at the mercy of Zone System.

If ZS contains subjectivity then why worry about metering, exposing, and developing so precisely? Why not just create your artistic expression in the computer or in the darkroom? The truth is, that you can’t fix everything in post whether capturing on digital or film. Even if correction is possible there would be a noticeable impact on image quality. You, as the artist, should be in charge of maintaining your vision throughout the process. Patience is promoting a careless attitude toward the early steps in a process because ‘you will change it in post anyway because it’s all subjective.’ This is a defeatist stance that places photographers at the mercy of their own tools. What ZS books stress in the opening chapters is that the photographer should strive to understand their own subjective intentions and the photographic process to achieve their vision. Those who are interested in maintaining an intimate control of their process from soup to nuts tend to use the ZS or some modification of it. In contrast I would argue that it is subjective - which is why we experiment, test, and calibrate our materials to achieve our subjective vision.

3.7 – Conclusion: What Patience calls Zone System is not the Zone System

For someone who claims to have read The Negative and The Print and admires Ansel Adams’ technical expertise, Patience presents a distorted picture of the method and science. First, he has ignored how ZS works on a technical level and how it incorporates the artist’s subjective vision. Second, his skepticism that ZS fails to correlate tonality between subject and print requires hard technical proof which he fails to provide. The counterexamples he does provide center around improper explanations of light meters and how they work. Finally, he makes a number of bold assertions about photographic materials that are false or explained in Zone System books. Simply, the author is describing a sham Zone System to refute.

4.0 Sensitometry Claims

There are a number of claims I’ve separated because they deal less with ZS and more with the science of sensitometry.

4.1 – ISO is a “Minimum Value”

“The ISO rating (“box speed”) states the minimum value at which you will be able obtain a properly exposed negative.”

Nowhere in the ISO document for determining film speed for black and white negative film (ISO 6:1993) does it claim the speed rating is a “minimum value.” The ISO number is calculated off of a curve with a specified slope and from a density point, designated as Hm, above the base + fog. This point is commonly referred to as the minimum density point because it represents the lowest amount of usable density on the negative. This coincides with the point where a photographer would typically want to place the darkest shadow detail. (The minimum density point is around Zone II in ZS parlance.) The point Hm is used for calculating ISO, but that doesn’t make it the ‘minimum value’ as he claims.

Diagram 4.1 - ISO 6:1993 - Determining film speed for black and white negative film. Film speed is calculated from point Hm. Where m is located on the curve is the location of the lowest amount of shadow detail from a subject. This point coincides with Zone II in the Zone System.

The logic behind the ISO establishing standard 6:1993 is supported by many practical and aesthetic reasons. First, this is the fastest ISO that still provides 3 to 4 stops of shadow detail. This provides the photographer with an adequate amount of shadow detail while still allowing them flexibility to stop down or shoot with a high shutter speed. In actuality, the ISO on the box is the maximum value, not the minimum. Patience has the language backwards, which should give one pause before considering him an authority on this subject.

The ISO speed is not dogmatic since the photographer will change the exposure index for their film based on a number of factors including choice of developer, and subjective intentions. For example, Beyond the Zone System discusses artistic reasons for selecting a different speed point depending on the amount of shadow detail desired. (1988, pg. 39) Second, psychophysical tests made decades ago found that people preferred exposing a scene closer to the toe of the film curve because grain is less prominent. (Eggleston, 1984 pgs. 30-31. Todd & Zakia, 1969, pgs. 73-77.)

4.2 Overexposure = More Information

“The more exposure you give your negative, the more information it will hold.”

The truth is not as simple as Patience is portraying. Overexposing (or lowering your exposure index) is necessary if your negatives are thin. For most beginning photographers this is due to issues with metering, and/or a lack of calibration within their materials. The evidence (or lack of evidence) provided by the author in the previous sections explains his continual insistence that film should be overexposed. However, his simplistic correlation lacks accuracy when researching ZS and sensitometry texts.

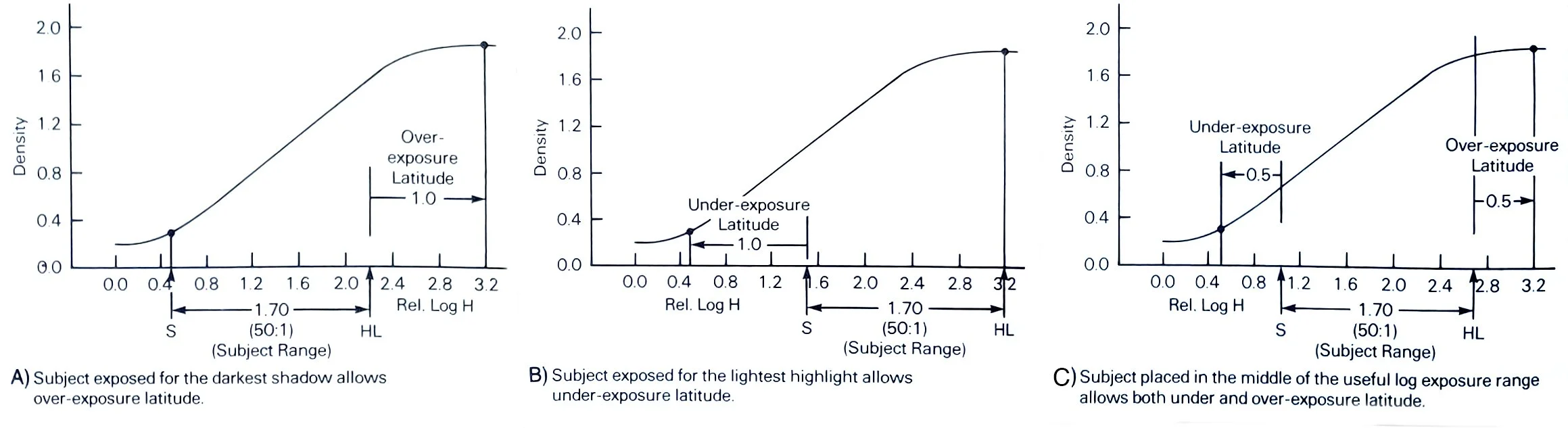

If you choose to expose your subject for the darkest shadow located at point Hm, the ‘speed point,’ than you are allowing for over-exposure latitude. In ZS language you are placing Zone II, where details in shadows disappear, at the minimum density on the curve. (Diagram 4.2, below, illustrates this fact.) However, you could also place the lightest highlight near the point where the film “tops out” with its maximum density. This is locating Zone VIII, where highlight details disappear, near the point of maximum density on the film curve. A photographer can also choose to place their subject’s information in the middle of the curve and balance the exposure latitude on either end. All of these possible scenarios are explained and understood through both sensitometry and ZS.

Diagram 4.2 - This illustration is from Basic Photographic Materials and Processes, 1st Edition. Graph A shows the conventional method of placing subject tonality near the lower part of the curve. This provides excellent tonal rendering with little grain. Graph B is another possibility, but would make grain more pronounced. Graph C shows a third possibility splitting the difference. Notice that film has upper and lower limits.

Notice in these illustrations that there is a lower limit and upper limit to the light a film emulsion can record. Patience claims that “the limit is never the negative” which contradicts the fact that all photographic materials have limits. A film/developer combination can only capture a determined range of information. The measure of the lowest recorded signal to the highest is the film/developer Dynamic Range and this will not change without altering the materials or development time in the process. Understanding that the author is struggling with shadow detail in what is, presumably, an uncalibrated process would entail the need to lower the effective film speed just to meet the threshold of placing the lowest shadow detail at the minimum density point. He is not “getting more information” but instead rescuing lost shadow detail and bringing his photographic process into alignment.

However, if you keep raising the exposure you run the risk of crushing highlight detail in the shoulder of the film curve. Therefore, the skillful photographer is interested in making sure they are placing their subject’s tones at an optimum place on the film curve for printing or scanning. Patience is performing the very advice espoused in sensitometry and ZS books, but turning it around as a criticism. For example, on the back of the book Photographic Sensitometry: The Study of Tone Reproduction it claims:

Diagram 4.3 - The marketing department certainly got involved with writing the back cover information for the book Photographic Sensitometry. These are true statements, but a more nuanced view is depicted inside the text.

If negative films can handle overexposure what are the drawbacks? As already mentioned there is a possibility of reducing highlight detail. Another significant change to image quality is increasing graininess because fixed pattern noise (aka grain) increases with exposure. These are two significant impacts to quality that Photographic Sensitometry, and many other books warn about. You are welcome to choose this process for aesthetic reasons if so desired. The impact to highlights and grain is demonstrated by Patience in a series of over and underexposed frames from a roll of Tri-X at this link. Notice that underexposure crushes shadow detail and creates milky blacks. From +6 overexposed and higher the grain is pronounced and highlight details are compressed.

Patience’s claim that ‘more exposure means more information’ is wishful thinking compared to explanations by sensitometry experts. Despite its sensational text on the back cover, Photographic Sensitometry more soberly admits that “a plot of print quality (as estimated by a panel of viewers) versus exposure index level indicates that there is an optimum. [The accompanying figures] show a reduction in print quality with both under and overexposure, but the reduction is more serious with under exposure.” (1976, pg. 169)

Patience’s most egregious statement comes at the end of his article when he claims that “A lot of things I am sharing in this article shouldn’t work according to the books. But they do, and they do so beautifully.” With the word beautifully he links to the under and overexposed images of Tri-X discussed in the previous paragraph. The problem is that his methods and claims are covered with greater accuracy and depth in books about Zone System and sensitometry.

4.3 The Larger the Film the Greater the Dynamic Range

“Large format sheet film, for example, has way more exposure latitude than medium format film. Medium format film has way more latitude than 35mm film, which again is a completely different story than a modern digital sensor. The size of the negative has a tremendous influence on the tonal range and the final result, be it a scanned image, a traditionally printed image or both. Dividing every image into 10 identical zones is a questionable approach, because the tonal response of a large format negative and a way smaller 35mm negative to the same exposure, the same amount of light, are completely different.”

Patience’s lack of knowledge extends to the design of photographic materials. In the paragraph above he equates larger film sizes to a greater dynamic range and therefore the number of zones that should be considered by the photographer. (For an understanding about the number of zones see my first Technical Sketch section 3.3.) However, looking at the technical publications for any available film stock reveals no difference in emulsion formula, but a change in thickness of the acetate base. For example, Ilford’s technical publication for FP4+ begins by describing the film and the different backings for each film size. The document only displays a single characteristic curve on page 5 because the emulsion, and therefore the tonal response, is the same for all format sizes. The technical publication for Kodak’s TMAX 100 is similar - there is no change in characteristic curves for size of format, but instead for different developing chemicals.

Without going too in-depth there are some reasons why Patience may believe that format size changes the tonal rendering. These are not inherent to the film format itself, but involve changes to the process surrounding the change in format size.

Different tank sizes causing changes to the volume of developer to area of film ratio.

Film development in a tank is different than tray developing sheet film.

Contact printing sheet film produces different print tones than enlarging film.

A psychological ‘feeling’ there is increased tonality due to the increased of detail with large format films.

There is also a strong possibility that he is responding to a difference in tonal rendering between Tri-X roll film (TX) and Tri-X sheet film (TXP). Kodak uses a different emulsion formula for 35mm and 120 film then that for large format film. However, notice that the curves for 35mm and 120 are identical when overlaid on each other.

Diagram 4.4 - On the left the curves for Tri-X 35mm and 120 are overlaid. Notice that they are identical because both use the same emulsion formula. On the right is the curve for Tri-X sheet film, which is a different emulsion formula.

The research required to confirm the emulsion formula for a range of format sizes is very simple. One doesn’t even need to buy, expose, develop, or analyze any of the materials download and read the pdf documentation from the manufacturer. This is further evidence of a genuine lack of research by the author. More importantly, the differences he is seeing, variations in the processes used between different formats, could be analyzed through the direct application of sensitometry or Zone System.

4.4 Out-of-Date Redux

“But I think it might be time to update the books and accept that what Adams suggested was solely made for the traditional darkroom printing process – born out of the problem that he had to find a way to compress 15 stops of dynamic range from a well exposed large format negative onto a sheet of paper that can only accommodate a total range of approximately 8 stops.”

The very reason that photographers care so much about the exposure and development of their film is precisely due to the fact that the final display has a limited range. This is not a problem that needs updating, but a part of the photographic process. I have explained this with references in previous posts in my Death of the Zone System series. For brevity I will state the major facts with the links to the posts which contain references to studies on the subject.

First, the dynamic range of the human visual system is tremendous if you are allowed the time to adapt to total darkness (which takes about 30 minutes) or to bright light. You experience this time lag walking from the sunny outdoors into a dark building and vice versa. Vision scientists worked with sensitometry experts to establish the dynamic range of the visual system when fixated on a photograph. The range (containing object detail) turns out to be around 8 stops when viewing a properly lit photographic print, or a computer monitor in interior settings. My writing with the data and citations are in part 4 of the Death of the Zone System.

If the visual dynamic range is only 8 stops this explains why so many display mediums possess the same range. Patience is correct that photochemical paper has an 8 stop range. (More accurately somewhere in the 7 to 8 stop range.) Many slide films contain an 8 stop range when projected. A properly calibrated computer monitor has 8 to 9 stops. (You can meter your own monitor to establish this fact.) This is why the number of Zones in the Zone System work so well across different mediums - it is based on appearance to our eye.

Negative films and digital sensors are designed to capture a large dynamic range in order to provide the photographer flexibility in the darkroom and/or computer. I cover how the range of tonality is captured and compressed in my How Zone System Works Part I and Part II. If you have not already read these I encourage you to do so because they explain the science and methods of these systems.

Patience is not leveling any criticism at Zone System or revealing cracks in the science of sensitometry. His statement that it was Adams who needed to find a way to compress 15 stops into 8 is historical fiction. The move from a larger DR in the capture medium to the compressed DR of the display is true for analog and digital and will continue that way until our visual system evolves.

4.5 Conclusion: Sensitometry Misunderstood

Johnny Patience’s explanations of sensitometry and its relation to Zone System are inaccurate and/or simplistic. He incorrectly explains how ISO is calculated and fails to understand that this is a manufacturer’s recommendation. His claims regarding photographic materials easily debunked by research online. By turning facts about the process of tone reproduction into criticisms and failures he is revealing he does not understand the content he is criticizing. The most revealing statement is the boastful “A lot of things I am sharing in this article shouldn’t work according to the books” when, in fact, his claims are covered in greater detail and accuracy in many books. One of his greatest discoveries, that negative film is forgiving when overexposed, is even used as a marketing blurb to encourage photographers to read a book on sensitometry.

Giving Patience the benefit of the doubt, perhaps he has read many wildly inaccurate books on sensitometry and Zone System. I don’t know where he found these books and who wrote them, but I hope he informs me of their titles and includes quotes. Another possibility, weighing the evidence Patience provides against the material cited, is that he read these books and just simply did not understand the concepts. There is also the possibility he never applied himself to any research or methodical study and is simply calling our bluff.

To be fair, when I began learning photography and darkroom printing I floundered a fair amount. There is a familiar ring when he writes that he “…researched the topic in depth, shot hundreds of rolls of B&W film, experimented with all kinds of exposure settings, chemicals and development formulas.” At first I believed trying numerous films, papers, and chemicals would improve my understanding of the medium. The results were all over the map because I was just using manufacturer recommendations. In hindsight I recognize that I was never properly handling any of these materials and making shallow judgments. (I criticized TMAX 100’s tonal rendering in front of John Sexton! Totally embarrassing in retrospect because my choice of exposure index and development time was the guilty culprit.) Fortunately, I encountered some excellent mentors who forced me to choose one set of materials and rigorously test them through the Zone System. I was also only allowed to change one link in my photographic chain at a time and only once understanding the consequences. The claim of testing hundreds of rolls of film and all kinds of chemicals sounds impressive. However, in my own experience, authorities on film photography can only usually speak to a narrow range of materials they use. On the other hand, they often spoke very clearly about the processes to understand any materials.

5.0 Patience’s Metering Method

Returning to the logical form of Patience’s argument we can answer whether there is any evidence that overexposing film is a violation of Zone System or the science of sensitometry. The answer is firmly negative (another pun intended) because of the sheer weight of published evidence that refutes Premise 2. Rather, the decision to overexpose film is treated by ZS and sensitometry and covered in numerous publications. There is experiential evidence as well if you choose to study and try Zone System methods. Don’t take Patience’s or my word for this - try it yourself.

Patience speaks highly of his metering method throughout The Zone System is Dead. Using the science of sensitometry and ZS I would like to explain his metering method in detail in order to put its purpose in proper perspective.

5.1 – Metering Method

“My metering method

I meter all color negative film the same. I use a very simple analog incident light meter (Sekonic L-398 A), nothing fancy or expensive. I rate my film half box speed. If I shoot Porta 400, that means I set the meter to ISO 200. Then I meter for the shadows, which means I bring my meter into the part of the scene that has the least light. If I don’t have a shadow anywhere close, I shade the bulb of the meter with my hand. I hold the meter in a standard 90 degree angle to the ground, which means nothing else than parallel to the subject, with the bulb facing the direction of the camera. That’s it.”

Patience’s Metering Method sounds simple because it is. He is metering in the shadows which would move the subject luminance range up by anywhere from two to four stops.

5.2 – Through the Lens of ZS and Sensitometry

Establishing a metering method that favors overexposure with negative films is easy to justify. First, the published ISO is established through ideal testing, but varies based on an individual’s process including their choice of printing materials. Helping others learn Zone System it is altogether too frequent that a student learns that their choice of film developer results in a loss of film speed. On the other hand, I have friends working with high acutance developers such as Rodinal who find their film gains speed. Johnny Patience uses Tri-X in XTOL developer and provides little information about his methods of handling the film. Searching for XTOL we can see in the comments that he uses XTOL in a stock dilution, but does not provide any developing time. However, he does admit that:

I don’t develop any of my film at home because of the volume I shoot. My lab develops and scans my work and then sends back my negatives. (23rd of October 2016)

Unfortunately, with no sensitometry graph from Kodak for Tri-X in XTOL, and the fact a lab is handling the development we have little information to go on. What we can surmise is that the film is losing speed since Kodak’s recommendations in its technical data for XTOL begins with an ISO of 400 and nothing lower. The Massive Development Chart does contain information for Tri-X in XTOL with a range of exposure indices and dilutions, but we would need to know what the lab is doing. (I considered sending a roll of film I exposed to his lab to make a sensitometric analysis of the negative and the scan. I acknowledge it is critical to my argument, but have little time at the moment to spare on this.)

Second, establishing a correct exposure index for a set of materials requires assiduous testing and observation. In my post on Zone System calibration I discovered that Agfapan APX 400 lost nearly two stops of speed in Pyro PMK. Patience provides no evidence of any attempt to calibrate his materials through Zone System. However, I believe that Patience has “observed his way” into a more calibrated photographic process by overexposing. For someone acquainted with ZS and sensitometry I can see from his complaints that he found his negatives thin and that shadow detail was a problem. He correctly followed the path of altering his exposure index and changing his exposure methods to improve image quality. At the same time, however, he denigrates the concepts that support his very decisions and would help him understand his materials and methods.

Patience’s recommendation to overexpose is only a useful recommendation or a rule of thumb. While it can be analyzed from a sensitometric or Zone System standpoint it is not a system or method, but really just an observation and easy way to get out of a jam. Zone System and sensitometry are systems of tone reproduction. As systems they incorporate a range of concepts in order to assist the photographer in understanding, calibrating, and executing the methods to create images. Patience’s metering method is a useful observation that generally works.

5.3 - Scanning

I am also under the assumption that the scanner has poor sensitivity to subtle changes in density in the toe of the film curve. Therefore, rating his film slower helps move the exposure more into the straightline portion which provides more density separation for the scanner to see and therefore more data to work with in Photoshop. Once again, he is expressing a legitimate adaptation of his process to better fit the limitations of the scanner. It would be interesting to see a scan of a Stouffer step wedge at different scanner settings to better understand the properties of the scanner.

6.0 – Conclusion

Consider Johnny Patience’s argument in light of the evidence from authorities on sensitometry and Zone System, as well as examples of the methods in practice.

Premise 1 – A photographer can achieve excellent results with negative film by overexposing it many stops above the manufacturer’s ISO.

This claim may be frequently true, but depends on many contingent circumstances. Patience is portraying this statement as a sweeping truth without context or nuance. A more statement would begin with ‘it is possible to achieve excellent results…’ which is more accurate and weakens the dogmatism of his stance.

Premise 2 – The results of Premise 1 are in direct contradiction to the concept and methods of using Zone System.

Sensitometry and Zone System as concepts and methods encompass not just the claim of the first premise, but a complete system of tone reproduction. The author’s insistence that these tools are the problem and not a solution goes beyond mere misunderstanding, but active dissemination of misinformation.

Keep in mind that Patience is making an argument concerning scientific processes. (These are processes in the service of an artistic vision, but ultimately scientific.) The burden of proof he is required to produce includes citations from texts along with technical evidence from following the disputed method. From the perspective of people conversant with sensitometry and ZS (such as myself and colleagues) it appears that Patience chose to show up to a battlefield without a single weapon. Claiming to have ‘read all the books’ and that the process ‘does not make sense’ is not evidence.

The faulty or inaccurate explanations of sensitometric principles, ZS method, and the behavior of photographic materials reveal this piece is not so much a requiem for Zone System as a monument to Patience’s mistaken ideas. One could go so far as to say that he did not only forget to bring a weapon to the battlefield, but did not show up to begin with. He is on a Quixotic quest to attack some shadow Zone System he believes is the enemy all the while overselling his metering method as simple solution to a complex problem.

By deciding to put information online we owe a huge amount of responsibility to the greater photographic community. Too often I find people struggling with Zone System (it’s a long learning curve!) and the poor information online only further confuses the process or summarily relegates it to the trash heap. We have to be careful when we make claims, and I’m more than willing to produce more evidence in the form my own tests, sensitometric data, and research to back up my claims. (I figure e-mails I receive with questions or arguments can lead to future posts.)

At the end of the day this is where I find Johnny Patience’s article the most troubling beyond the technical inaccuracies and logical fallacies. I really love his concluding paragraphs where he expresses the importance of making the photographic process service the creative vision and the need to test claims for ourselves. However, Patience’s assessment of Zone System fails to follow in the same generosity of spirit he expresses and becomes a lost opportunity. If he solicited advice from users and experts to weigh in on each problem he encountered with ZS his blog would become profoundly educational. Instead, he chose to denigrate ZS and sow confusion with personal mythologies.

6.1 Where does Freedom Come From?

As a final thought I want to present a different approach to the art of photography then the one Johnny Patience espouses. He invokes a need for freedom, specifically a freedom from technicalities.

“With practice you will be able to guess your exposure, which removes all technicalities and for me, is the ultimate freedom. Nothing needs to stand between your vision and your final result.”

“…it’s all about freedom. Sometimes even freedom of thought.”

Personally, Patience’s ‘freedom from all technicalities’ and ‘freedom of thought’ sounds more like avoidance. The photographic arts is one of the most technologically complicated mediums. It not only encompasses a broad range of the physical sciences, but involves a large number of processes to capture, process, and display an image. On a technical level, the photographer simply cannot choose whether to engage with sensitometry, optics, chemistry, etc - they are along for the ride whether you like it or not. Conceptually, the artist must make an honest effort to engage and understand the methods and ideas of others. ‘Freedom of thought’ is not genuinely embodied by a flawed understanding and characterization of Ansel Adams’ method or views. Instead, Patience’s The Zone System is Dead reads as if he is prisoner to his own beliefs.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that learning photography must begin with everyone learning hard physics. Many start with the camera in automatic settings and focus on optics and composition to begin. What I am claiming is that anyone wishing to deepen their skill and craft will ultimately seek out further topics which, alas, are technical in this art. You are welcome to choose how deep you want to go. What I do not recommend is stopping short and claiming everything deeper is incorrect because you chose not to engage it.

What I contend is that learning the science and technology is the way to find freedom. Freedom is found through the technicalities. Freedom is found through understanding another person’s ideas before forming one’s own. Freedom involves engagement, not dismissal.

Cited Books:

Adams, Ansel, The Negative. Little, Brown and Company: Boston, 1981.

Adams, Ansel. The Print. Little, Brown and Company: Boston, 1983.

Adams, Ansel, and Mary Street Alinder. Ansel Adams: An Autobiography. Little, Brown and Company: Boston, 1976.

Davis, Phil. Beyond the Zone System, 2nd Edition. Focal Press: Boston, 1988.

Eggleston, Jack. Sensitometry for Photographers. Focal Press: London, 1984.

James, T.H., ed. The Theory of the Photographic Process, 4th edition. Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.: New York, 1977.

Stroebel, Leslie, et al. Basic Photographic Materials and Processes, 1st edition. Focal Press: Boston, 1990.

Todd, Hollis N. and Richard D. Zakia. Photographic Sensitometry: The Study of Tone Reproduction. Morgan & Morgan, Inc.: Dobbs Ferry, 1969.

White, Minor, et al. The New Zone System Manual. Morgan & Morgan, Inc.: Dobbs Ferry, 1976.