Tea Developed Black & White Film (Part I)

Life in the Weeds

In researching material for Science of Cinematography I have reached a peculiar point where most of my time is spent in the weeds. If you spend time outdoors you have surely had the experience where the idyllic calm of the woods is broken by an uninvited perturbed rustling that sets the heart racing and the imagination freewheeling. Timid investigation reveals not a mountain lion but a foraging squirrel who, disturbed in his labors, is just as surprised to see you. I’m that squirrel, although I’m more like a meadow vole in my unassuming poise, out foraging the technical literature of photography for god knows what, and sometimes also making a goddamn racket.

The advantage of being out in the weeds is that eventually one returns to the manicured lawns of civilization with knowledge that proves useful. It’s not unlike desiring to know the best places for grasses and forbs and having a vole at hand to give a satisfactorily delicious answer. A current example is a project my partner, Erika Houle, has begun to photograph members of the Global Tea Hut community in New York with black and white film that is developed in tea.

Looking Back

My past experience with tea as a developer had measured success leaving only one critical obstacle hanging in the balance. In the earlier years of teaching my course I used to begin the Photochemistry class by taking photos of my students. I used Efke 25 film and a 2K tungsten unit within 3 feet of their faces to get exposure. (I used 25 EI film largely because this slow emulsion had a quick development time.) At the point in the class where I discussed the chemical process I would produce a bottle of Teas Tea green tea to use as the developer, a bottle of lemonade to stop development, and a can of tomato juice as a fixer. Much of this was a show because, as I was forced to reveal, the tea in the bottle was actually green tea I boiled at home to extract every ounce of chemistry and to which I added Sodium Carbonate as an “accelerator” to get development times down to a reasonable length. Also, I never fixed in tomato juice because it would give the negative a strong red stain. However, stopping development in lemonade was both successful and delicious.

The first tea developed negatives shown on a light table. Notice the unusual orange-brown color of the base + fog.

Achieving a dense negative proved not to be the problem, but rather printing the negative. Much to my chagrin no matter how I changed the printing time the image of the students never appeared - only a black and empty frame. I felt as if I had captured a photo of Dracula only to discover his visage was as unprintable as it is catching his reflection in a mirror.

Step print to determine the standard printing time for the tea negatives. You can see the slightest image of a face in the lighter portions of the print.

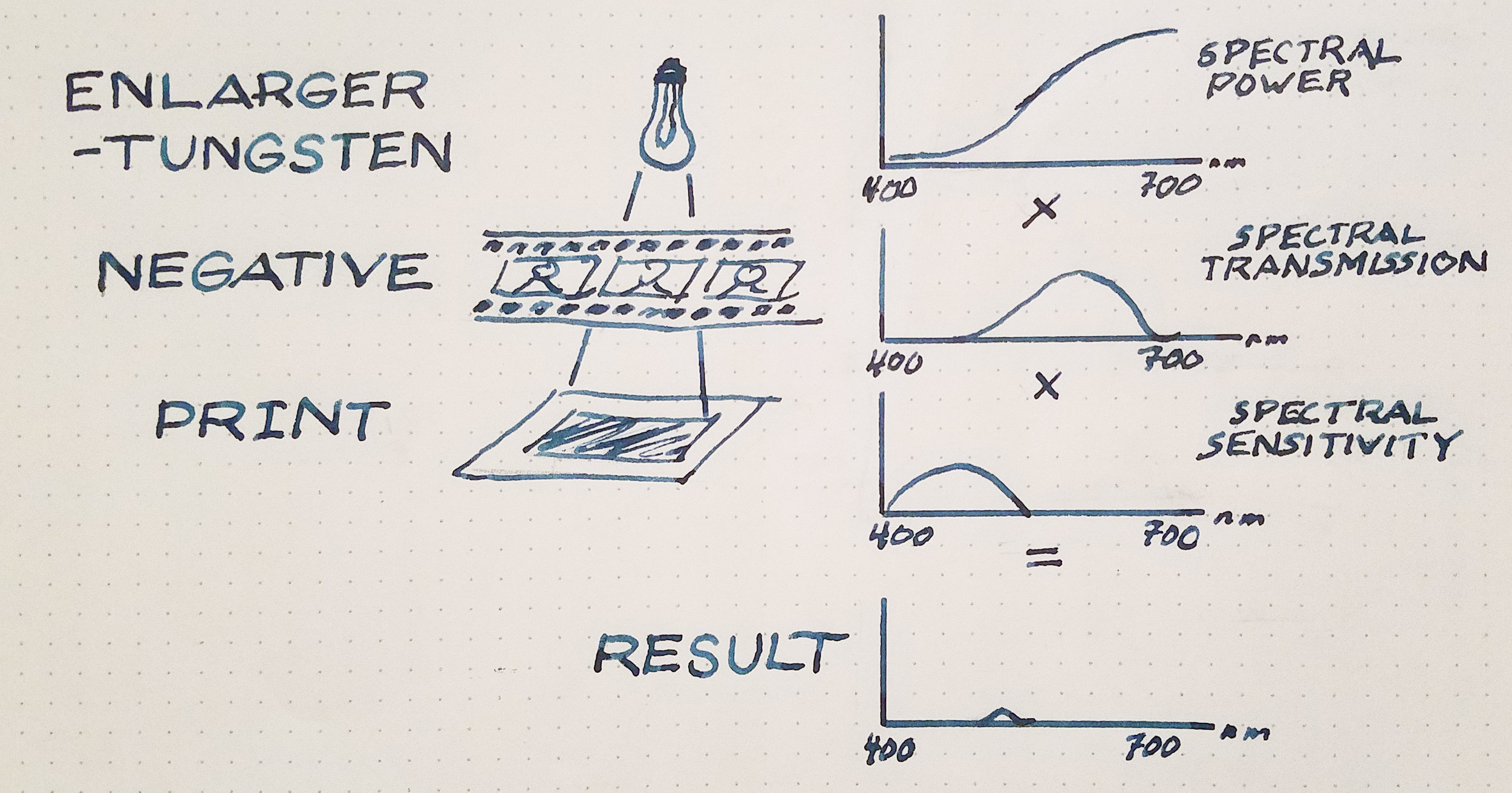

As I thought through my process I realized something was amiss between the color sensitivity of my materials and the fact my negatives possessed a deep orange stain from the developer. My light source in the enlarger was tungsten and my negatives were orange so this meant plenty of light, albeit orange in color, was reaching the paper. Then, I realized I had never looked at the spectral sensitivity diagrams of Oriental Seagull GF paper.

Oriental Seagull Graded Paper spectral sensitivity graph. You can see how it is only sensitive to blues and some blue-greens.

The orange base + fog meant the paper was blind to the image on the film.

My next solution was to try and contact print the negatives in the Sun. My hope was that the more even spectrum of daylight would mean a greater amount of blue light could penetrate the negative. I ran outside and flashed the film and paper quickly. However, this only produced the barest ghost image of a face.

A strip of the negatives flashed in direct sunlight. Once again you can see just the ghost image of the faces. This shows how much blue light was absorbed by the negatives and therefore never reached the print.

The eventual solution was to hand the negatives to a friend at a photo lab who could print them through a color process. The paper for color is much more full spectrum and the orange stain posed less of a problem because it is not too dissimilar to the orange integral color mask of color negative film. Eventually, I had my images and the additional bonus of a great science lesson for my students.

Finally, an image. Tea developed negative printed to color paper through a commercial machine.

Moving Forward

So time in the weeds produced valuable information and demonstrated future success is possible. I had an inkling the color cast originated from the Sodium Carbonate since its addition to the brown colored tea instantly turned it orange during mixing. This provided hope of success with Erika’s project as well as a starting point for our own tests. If we could eliminate the orange stain problem then we could move on to more prosaic task of matching development time to paper contrast and make beautiful prints. At the time I couldn't work out a good tea developer because my life dictated moving onto another patch of weeds. To be precise, I had to delve into a patch of digital weeds as I worked on keeping up with the analog to digital transition.

I have encountered those using this “in the weeds” in a negative sense (no puns intended), as if there is little use to far-flung journeys in remote places. Rather, these are educational opportunities for deep study as well as experiment, the mother of invention. Even though developing film in tea tea was a sideshow attraction to the much greater topic of cinematography I could have never guessed this errant journey would be relevant in the future. So I derive some satisfaction with the work itself, and eight years later being able to dredge up my story from memory in order to assist someone in their artistic process.