Death of the Zone System (Part II)

(“Death of The Zone System” is a series about the relevancy and shifting attitudes towards Ansel Adams and Fred Archer’s Zone System.)

Part II - A Personal Journey through the Zone System

Before I delve into the claims made today about the Zone System, I think it helps to take a step back and appreciate what knowledge ZS practitioners have about their materials and how they obtain this knowledge. I initially began writing this post explaining the historical development (all puns intended) of sensitometry and Zone System but quickly realized this would probably induce somnolence. I hope my own story to become a competent photographer is not taken as solipsism but illustrates how the acquisition of in-depth knowledge can improve one's photography.

PHASE 1: Ignorance with Moments of Insight

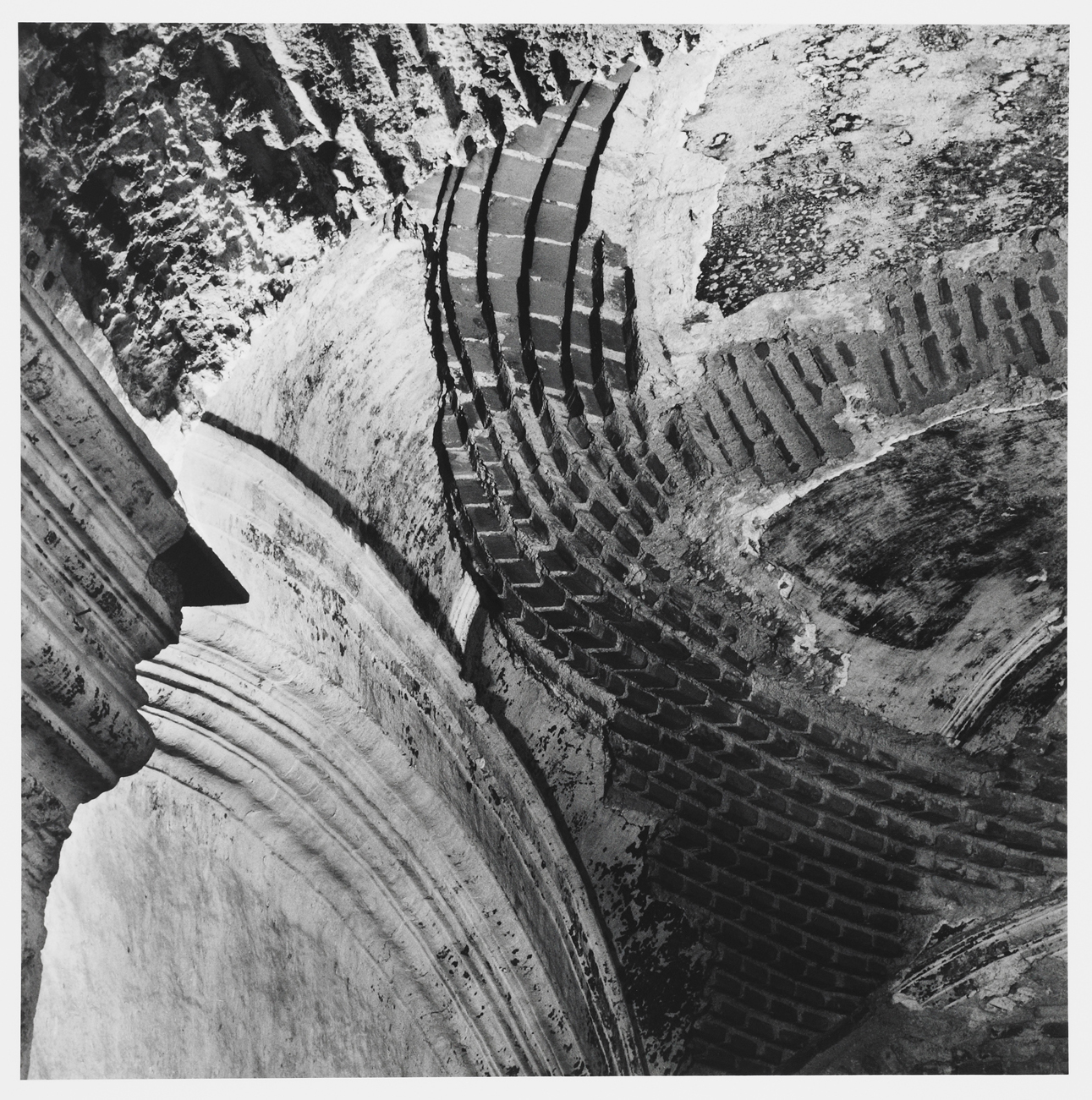

When I first started learning black and white photography my first struggles involved getting a properly exposed negative. From there I would take my battle into the darkroom to create the image I thought I had captured in the first place. I remember at this time each press of the shutter was a moment of uncertainty and the darkroom was a void where I fought to reverse the mistakes of the past. I have kept a handful of prints from this time. Below is the first photograph I thought was “great.” I took it with a Nikon F3T and a 50mm lens on Tri-X inside of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. It was difficult to hand hold the camera for the 1/30th of a second exposure, but I photographed it enough times to get a sharp negative.

Scan from original print. I took this photo some time back in the late 1990s.

I developed the film in Rodinal and if I remember correctly (the negative is lost) it was fairly low contrast and probably a bit underexposed. Still, I had all the tools on hand to remedy this in the darkroom. I shortened my printing time, I used a multigrade paper at either grade 4 or 5 in order to get a deep black. Still, the image was lacking substance because the all the tonal values were low (except the window). So I discovered I could dodge and burn separate areas to draw out distinctions between the different areas of vaulting. I remember a particular problem was with the foreground pillar, which was dinghy gray and ominous, and I solved this by cutting a dodging tool exactly to the shape of the pillar in order to bring it up to a more luminous value. Sadly, I’ve lost my dodging and burning map but I can recall it looked something like this:

The more I look at this mental recreation of my dodging and burning map the more I think this looks too simple. It was very hard to print and required a large number of dodges and burns to extract the subtle gradations that are in the final print.

I created a print that at the time I was very proud of, but making several identical prints resulted in a large number of mistakes and rejects. I knew this was no way to work, but I didn’t understand how to improve. The problem was that occasionally, even as an amateur, I would get a beautifully exposed negative that was easy to print. In retrospect it is obvious that in the sheer volume of exposures you make as an amateur you will inevitably take a good photo, captured under the right lighting circumstances, developed correctly, and easy to print such that you are left writing off the other images as uncontrollable mistakes. And yet, I didn’t want to write off many of the images I was taking due to technical mistakes. I wanted my images to not always be a struggle to print. Fortunately, I was friends with a number of extremely accomplished photographers who helped guide me through the process of understanding my tools. What it required was some testing.

PHASE 2: Discipline through Testing

Even though I had read Ansel Adam’s The Negative and The New Zone System Manual nothing was more helpful than when my friend Dwight Primiano sat down with me and spelled out the entire test method.

Step one was to pick a set of materials (film, developer, paper, darkroom chemistry) and stick with only these materials until I genuinely felt the urge to change something. A common neophyte mistake is to constantly change film, developers, papers without first learning how any one of them behave. I settled on a system and then had to perform the instructed tests. This took only a weekend and required shooting out multiple rolls of film. I had to determine Standard Printing Times for each film, the Effective Film Speed of each film, and then photograph a representative scene with five rolls and develop each at different times in the effort to establish a normal development time. I don’t want to make this post any longer by explaining the test in detail, but I still have all my work from that weekend.

Practical Zone System tests to establish standard printing times (print strips are in the folder at the top) and effective film speeds of APX 100 & 400.

Everything I learned that weekend is posted below. Most importantly was the discovery that my problems with thin negatives stemmed from the fact my film lost speed in the older PMK pyro developer. My 100 speed needed to be exposed at an index of 12, and my 400 speed became a 125. I was also establish normal development times so that my tonal scale carried a rich palette from white to black. What I learned was as follows:

APX 100 - EI: 12 - DevelopingTime: 11 minutes - Printing Time: 15 seconds

APX 400 - EI: 125 - Developing Time: 16 minutes - Printing Time: 24 seconds

Even though this test did not give me data about how to alter my exposure and development time for scenes with low or high contrast, it gave me a useful set of practices to photograph in scenes of normal contrast. I immediately discovered that the number of images that were easy to print increased dramatically. My time in the darkroom wrestling with an image dropped and I was proud of the quality I was achieving.

Photographed on a Mamiya C33 with a 135mm lens at f/8. The exposure was 15 minutes with APX 100 in PMK pyro. Printed on Grade II FB Oriental Seagull. I never realized the similarity between this and the previous photo until I started writing this entry. This negative is much easier to print. The only difficulty is in burning down the wall on the left that is receding behind the column.

By also reading about Zone System I also learned the first and most important step of any visual art process, Previsualization: that a well-realized image is first seen in the mind’s eye of the artist. Once the artist’s vision is harmony with their knowledge of their tools they are no longer at the servitude of the medium, but rather begin to express their ideas more purely through aesthetics. I felt closer to the precipice of a photographic truth.

PHASE 3: Peeling Away Layers of the Onion

When a photographic system is calibrated it’s exciting to make prints that are nearly perfect at the standard printing time alone. Certainly this makes life easier and wastes less materials, but it also gives you time and energy to use dodging and burning as a means to finesse very fine details.

However, at this point I realized I was still not fully in control (and not really practicing Zone System) because I did not have information for expanding or contracting development for different lighting scenarios. While I appreciated the practical testing methods I had learned I wanted a more comprehensive and scientific method of understanding my tools, and of the hard numbers and charts that back up my experiences.

By far the best book I found was Phil Davis’ Beyond the Zone System, a book whose title is incredibly accurate and misleading at the same time. I find many photographers upset that it does not contain an updated ZS that is easier to understand and use. However, this is not what the author intended when he used the word “beyond,” but rather that this is the sensitometric science beyond Zone System.

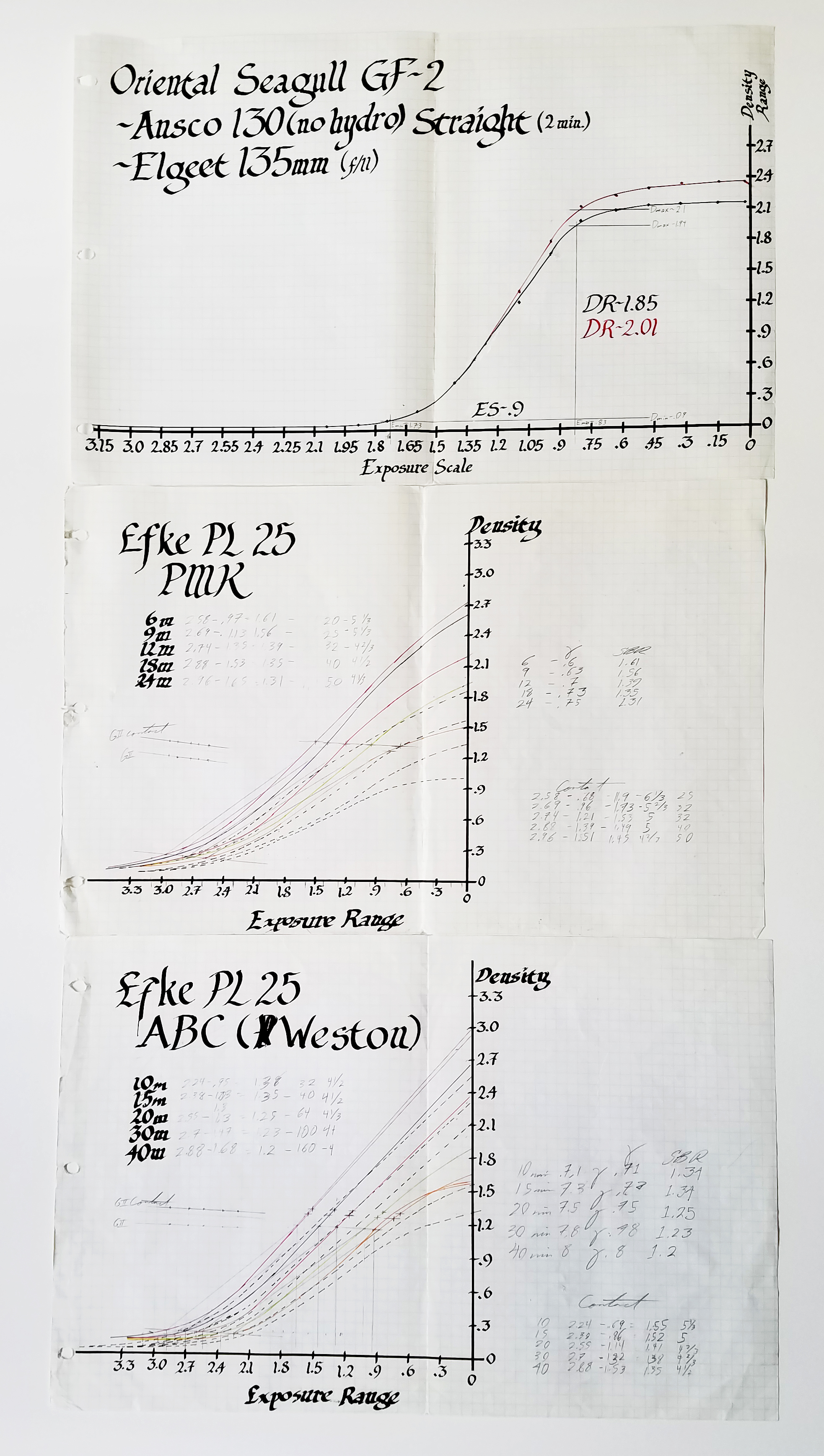

After digesting the rather difficult information I did eventually find it easier to test my materials by contact printing a step tablet to five pieces of sheet film, developing these sheets at different times, reading them on a densitometer and plotting the results. (I know this does not sound easy but it is because you use less film, spend less time in the darkroom, and the major task becomes creating graphs.)

Densitometer with enlarged step tablets on Seagull GF-II, and contact printed step tablets on Efke 25. This was my system before the discontinuation of both of these products.

Once all this data is graphed one can immediately relate the exposure range of your paper, to the density range of the negative and extract a range of useful charts showing how to rate the film speed for different contrast ratios, and what developing time is optimal.

My sensitometry charts for my paper and film. You can see my propensity for doing things by hand.

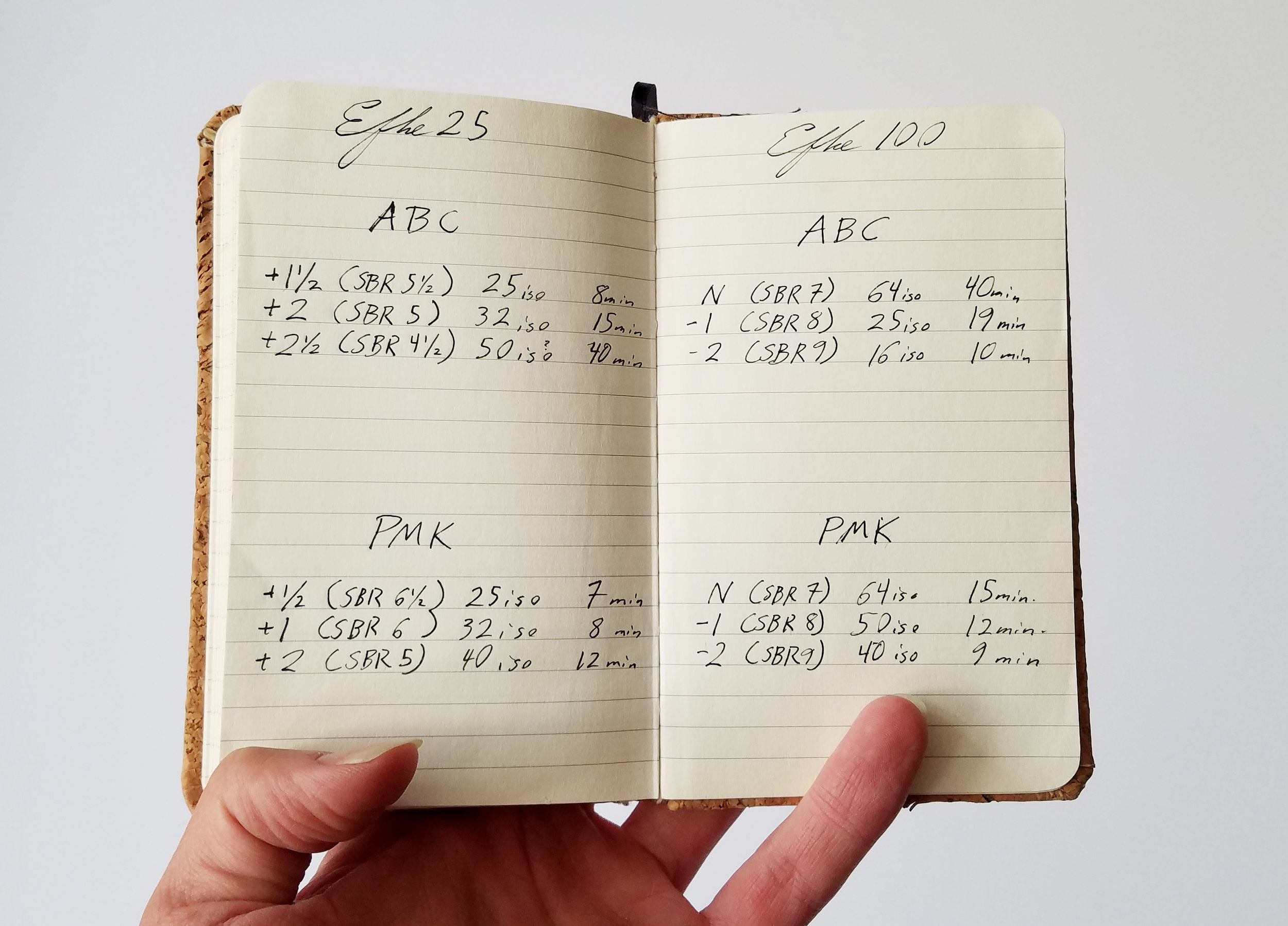

A page from my notebook I would carry in the field. You can see that depending on the contrast ratio of the scene I would use different developers. You can also see how inherently contrasty Efke 25 is (I could never really pull it in development) versus Efke 100 which was hard to push develop but easy to pull.

This method is abstracted from the working practices, but I quickly found myself able to walk outside with a simple set of notes, photograph a negative, and get extremely good results. I started to make prints like this

8x10 contact print on Seagull GF-II. The print is beautiful at the standard printing time and my only adjustment is dodging the foreground rock up by a few seconds. Shot with the Wisner Technical Field through a 12" Bausch & Lomb Protar (uncoated!) onto Efke 25. Exposure time was probably 2 seconds at f/32.

While many people get a good chuckle out of the process of using a densitometer to make all these charts I have never looked back on these efforts with any regret. First, my understanding of how my materials behave under different circumstances and how to control them became comprehensive. I was also able to leverage this knowledge to help answer further questions about the effects of selenium toning to image quality, and also investigate the effects of bromide drag when developing a print. Second, armed with my notebook I never had to second guess myself on a technical level. My experience of making a photograph became exactly that: making. I could concentrate on the aesthetic decisions of my work.

Not Mastery but Competency

My own learning was the reverse order of the history of photographic science, I learned Zone System first and then sensitometry. While sensitometry is the root of Zone System I understand why the majority of photographers will not begin by wading through this intense science: sensitometry requires a device many photographers don’t want to purchase, is very analytic, and also does nothing to help relate the process to visual perception. This is why the Zone System remains such a powerful tool in that it gives you practical testing methods to understand your materials, is possible to understand without an intimate knowledge of sensitometry, and helps you relate it to your sensory perception. The work by Adams and Archer is comprehensive, coherent and also applicable to digital. So why does it appear that less and less photographers understand it, or care to use it?

My next posts will take a close look at the current books about "Digital Zone System" and the comments on-line that I find contain a great number of misconceptions and ultimately fail to help amateur photographers. Ultimately, I hope to take a close look at Zone System to demonstrate its relevancy despite advances in camera technology, automation, and image manipulation software.